The science behind meat curing has fascinated food chemists for centuries, with sodium ion migration playing a starring role in this ancient preservation method. When we examine the osmotic pressure model that governs how salt penetrates muscle tissue, we uncover a remarkable interplay between physics, chemistry, and culinary tradition that transforms raw meat into savory, shelf-stable charcuterie.

The cellular dance of sodium and water begins the moment salt meets meat. As sodium chloride crystals dissolve in the meat's surface moisture, they dissociate into positively charged sodium ions and negatively charged chloride ions. These charged particles create what physicists call an ionic concentration gradient - essentially an invisible slope down which the ions want to slide. The steeper this gradient (meaning the greater difference between surface salt concentration and interior salt concentration), the more forcefully the ions will migrate inward.

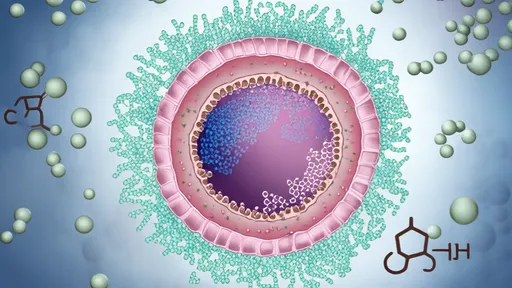

What makes this process particularly fascinating is how it defies simple diffusion. Unlike neutral molecules that spread randomly from high to low concentration, charged ions like Na+ engage in a more complex migration pattern. They must maintain electrical neutrality as they move, meaning chloride ions follow sodium ions in what becomes a coordinated cellular invasion. This paired movement creates the foundation for the osmotic pressure differential that drives moisture exchange.

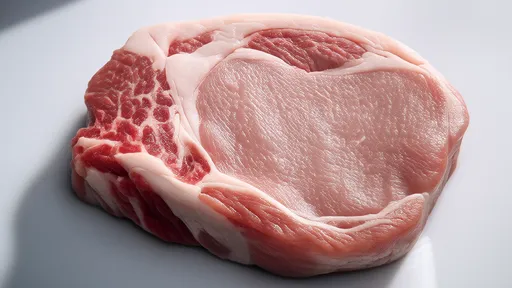

Osmotic pressure emerges as the true architect of cured meat's transformed texture. When the salt solution outside muscle cells becomes more concentrated than the fluid inside, nature seeks balance. Water molecules inside the cells feel the pull of this concentration difference and begin exiting through semi-permeable cell membranes. This outward flow continues until either the concentrations equalize or the increasing internal protein concentration creates enough counter-pressure to stop the process.

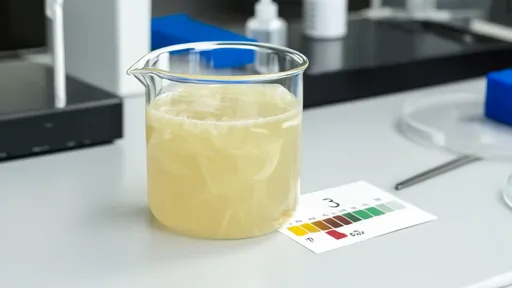

The brilliance of traditional curing methods lies in their empirical understanding of this equilibrium. Old-world charcutiers may not have known about ion gradients, but they perfected salt concentrations that remove just enough water to preserve without desiccating. Modern research shows their 3-5% salinity targets create osmotic pressures of about 25-30 atmospheres - sufficient to inhibit most bacterial growth while maintaining palatability.

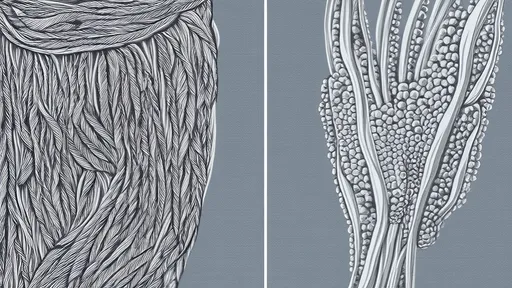

Muscle structure dictates migration pathways in ways that explain why different cuts cure at varying rates. The parallel bundles of muscle fibers create natural channels for ion movement along their length, while the perpendicular connective tissue sheets act as partial barriers. Electron microscopy studies reveal sodium ions moving about three times faster along the grain than across it, a fact that informs how butchers traditionally cut meat for curing.

This directional migration becomes particularly important in whole-muscle cures like prosciutto or country ham. The salt must travel centimeters rather than millimeters, requiring months of patient waiting. During this extended cure, the sodium ions gradually displace potassium ions in muscle cells through ion exchange mechanisms - a subtle biochemical shift that contributes to cured meat's distinct flavor profile different from simply salted meat.

The temperature paradox presents an interesting twist in the osmotic narrative. While heat accelerates most chemical processes, meat curing operates best just above freezing. This counterintuitive preference stems from two competing factors: ion mobility increases with temperature, but protein structures that facilitate migration begin breaking down. The sweet spot around 4°C (39°F) maintains membrane integrity while allowing sufficient sodium ion movement.

Modern curing facilities use precisely controlled refrigeration to optimize this balance, but traditional cellar curing achieved similar results through seasonal timing. Winter curing wasn't just practical for preservation - it unknowingly provided the ideal temperature range for controlled ion migration. The slow, steady penetration allowed full muscle saturation without surface over-concentration.

Concentration gradients tell only half the story of this complex biochemical ballet. As sodium ions displace calcium ions bound to muscle proteins, they cause subtle structural changes that affect water-holding capacity. This ion exchange explains the firm yet moist texture of properly cured meat - the proteins rearrange just enough to retain some moisture while expelling excess liquid. The process resembles a carefully choreographed molecular dance where each ion knows its place.

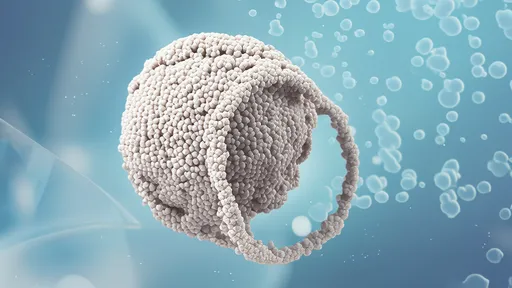

Advanced imaging techniques have revealed how sodium ions preferentially bind to specific sites on myofibrillar proteins. These binding events cause the proteins to partially unfold, creating a gel-like network that traps water molecules in microscopic pockets. This explains why well-cured ham stays succulent despite significant moisture loss - the remaining water becomes molecularly "organized" in ways that resist evaporation and microbial access.

The sugar factor in many curing recipes isn't just about flavor balance. Sugars like dextrose or sucrose modify the osmotic pressure equation by contributing their own solute particles. While they don't dissociate into ions like salt, their presence affects water activity - a critical measure of available moisture for microbial growth. The combination of ionic and non-ionic solutes creates a more complex osmotic environment that some researchers compare to biological fluids.

This dual-solute system helps explain why certain traditional cures use honey or fruit juices. Beyond their flavor contributions, these natural sweeteners provide a spectrum of sugar molecules that interact with the sodium chloride to create unique osmotic profiles. Artisanal producers often speak of "balanced cures" - an empirical understanding of how different solutes work in concert to achieve optimal preservation and texture.

Modern computational models now allow us to simulate the curing process with remarkable accuracy. Food engineers use finite element analysis to predict salt penetration rates based on muscle structure, fat content, and curing conditions. These models confirm what experienced curers have long known empirically - that uniform salt distribution requires time more than concentration. A moderate brine given weeks outperforms a heavy salt rub given days.

The latest research explores how pulsed electric fields or ultrasound might accelerate ion migration without compromising quality. Early results suggest these technologies can enhance salt penetration by temporarily increasing membrane permeability, potentially reducing curing times for certain products. However, traditionalists argue that the slow dance of ions through muscle tissue contributes to flavor development that can't be rushed.

As we continue unraveling the complexities of sodium ion migration in meat curing, we gain not just scientific understanding but deeper appreciation for this ancient preservation method. The precise interplay of osmotic forces, ionic bonds, and cellular structures transforms simple ingredients into culinary treasures through what amounts to a months-long biochemical symphony. Each slice of well-cured charcuterie represents a triumph of physics and chemistry harnessed by human ingenuity.

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025