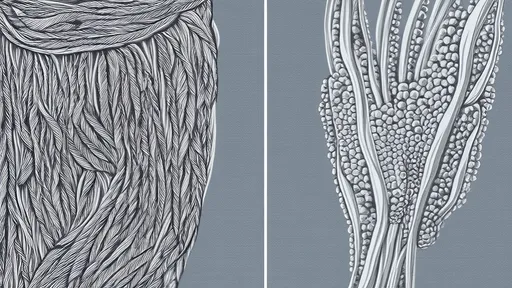

The tenderness of beef cuts has long fascinated both culinary experts and meat scientists alike. Among all the factors influencing meat texture, the density of muscle fiber bundles stands out as a fundamental anatomical characteristic that creates dramatic differences between tough cuts like beef tendon and tender cuts like tenderloin. This structural variation explains why these two muscle groups behave so differently during cooking and mastication.

At the microscopic level, beef tendon presents an exceptionally dense arrangement of parallel collagen fibers that form tight, rope-like bundles. These structures evolved to withstand tremendous mechanical stress during the animal's movement, creating a cross-linked matrix that resists separation. When raw, the tendon's translucent appearance hints at this dense architecture - the fibers pack together so tightly that light struggles to penetrate between them. This extreme density translates directly into the chewiness that characterizes tendon in dishes like pho or stews.

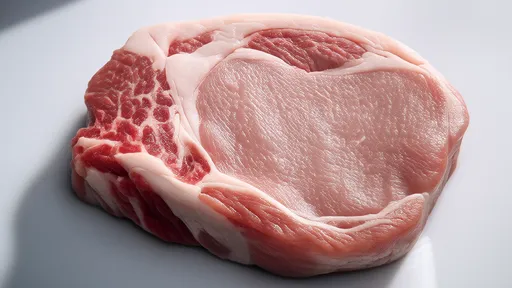

In stark contrast, the tenderloin muscle (commonly called filet mignon when cut) reveals a completely different fiber organization under magnification. The muscle fibers arrange themselves in loose, small bundles separated by generous amounts of intramuscular fat and connective tissue. These wispy bundles resemble scattered straw rather than tight ropes, allowing the fibers to separate easily during cooking. The pale pink color of raw tenderloin visually demonstrates this open structure, with visible marbling between muscle groups.

The functional demands placed on these muscles during the animal's life created this divergence. Tendons function as biological cables that transfer force from muscles to bones, requiring maximum tensile strength. Every movement from walking to kicking engages these structures, demanding dense collagen reinforcement. Tenderloin muscles, however, serve primarily as stabilizers rather than prime movers. Their limited workload permitted the development of this delicate architecture without compromising the animal's mobility.

Cooking transforms these anatomical differences into sensory experiences. When heated, the dense tendon collagen first tightens then slowly converts to gelatin over many hours of moist cooking. Even after this transformation, the remaining fiber structure maintains noticeable resistance to chewing. Tenderloin responds entirely differently - the loose bundles coagulate quickly at medium temperatures while the abundant fat renders, creating that characteristic melt-in-the-mouth texture prized by steak lovers.

Butchering techniques further emphasize these inherent differences. Skilled butchers carefully remove the silverskin membrane from tenderloin to prevent any additional chewiness, while tendon often gets sliced thinly across the grain to shorten those dense fiber bundles. These preparation methods work with the meat's natural structure rather than against it, demonstrating how understanding muscle anatomy informs culinary practice.

The implications extend beyond the kitchen. Meat scientists use fiber bundle density measurements to predict tenderness scores, helping producers optimize breeding and feeding programs. High-density muscles like those from the shoulder or leg require different aging protocols than loose-fibered cuts. Even modern plant-based meat alternatives attempt to replicate these structural differences when creating products meant to mimic various beef textures.

For consumers, recognizing these anatomical clues can guide purchasing decisions. The visible grain pattern on raw steak indicates fiber bundle orientation - tightly packed parallel lines suggest more chewiness while indistinct grain hints at tenderness. Understanding that density translates directly to texture helps explain price differences between cuts and informs optimal cooking methods for each muscle type.

This structural understanding also demystifies why "low and slow" works for some cuts while others demand quick, hot cooking. Dense fiber bundles need time for collagen breakdown, while loose bundles risk drying out with prolonged heat. The animal's anatomy thus writes the recipe long before the meat reaches the kitchen, with fiber density serving as the primary author of texture.

As research continues, new findings about muscle microstructure may further refine our understanding of meat tenderness. Advanced imaging techniques now allow scientists to map fiber bundle density in three dimensions, revealing variations within single muscles that explain why certain sub-primals contain both tender and tough sections. This knowledge helps butchers make more precise cuts and assists chefs in optimizing preparation methods for every part of the animal.

The story of beef tenderness ultimately unfolds at the microscopic level, where the simple principle of fiber bundle density governs our dining experience. From the stubborn chew of well-exercised muscles to the yielding softness of underworked ones, anatomy dictates enjoyment in every bite. This biological truth reminds us that exceptional cooking begins with understanding what lies beneath the surface - in this case, quite literally.

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025