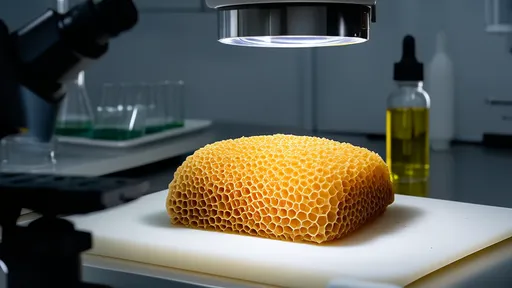

The transformation of collagen into gelatin during the slow cooking of beef tendons is a fascinating interplay of chemistry, temperature, and time. This process not only defines the texture of dishes like braised beef tendon but also unlocks nutritional benefits that make it a prized ingredient in both traditional and modern cuisine. Understanding the precise thermal breakdown of collagen reveals why certain cooking methods yield superior results.

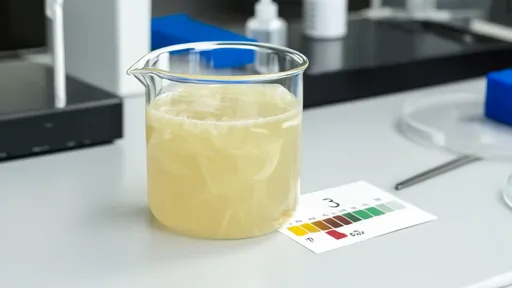

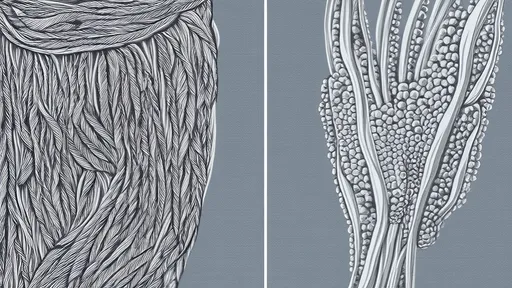

Collagen, the most abundant protein in connective tissues, provides structural support to muscles, tendons, and ligaments. In its raw form, collagen is tough and fibrous, making it nearly inedible. However, when subjected to prolonged heat in a moist environment, the triple-helix structure of collagen denatures and unravels into gelatin. This metamorphosis occurs through hydrolysis, where water molecules break the peptide bonds holding collagen's polypeptide chains together. The resulting gelatin gives braised dishes their characteristic unctuous mouthfeel and rich viscosity.

The critical temperature range for gelatinization begins around 60-70°C (140-158°F), where collagen fibers start to shrink and lose their structural integrity. However, efficient conversion requires sustained temperatures between 80-95°C (176-203°F), as found in simmering liquids. At these temperatures, the hydrogen bonds and cross-links between collagen fibrils progressively dissolve over several hours. Professional chefs often maintain temperatures at the lower end of this spectrum (around 85°C/185°F) to achieve optimal gelatin extraction without causing excessive muscle fiber toughening.

Different cuts of beef tendon exhibit varying gelatinization kinetics due to their collagen density and cross-linking patterns. Younger animals generally have less cross-linked collagen that converts faster, while older livestock require extended cooking. The presence of acidic ingredients like tomatoes or wine can accelerate hydrolysis by disrupting collagen's molecular stability, though excessive acidity may lead to undesirable texture changes. This delicate balance explains why traditional recipes across cultures—from Chinese niú jīn to Italian ossobuco—employ similar low-and-slow cooking principles despite differing flavor profiles.

Modern culinary science has refined our understanding of collagen breakdown through differential scanning calorimetry studies. These reveal that collagen's thermal denaturation isn't a single event but occurs across multiple endothermic peaks corresponding to different structural components. The first major transition around 60°C involves the unwinding of the collagen helix, while subsequent stages (up to 90°C) reflect the dissolution of more stable crystalline regions. This explains why insufficient cooking time—even at proper temperatures—results in incomplete gelatinization and residual chewiness.

The viscosity of resulting broths directly correlates with gelatin concentration, which peaks after 6-8 hours of simmering. Beyond this point, excessive thermal energy may degrade gelatin into shorter polypeptides, diminishing its thickening power. Skilled cooks monitor this by observing the broth's coating ability on utensils or checking tendon tenderness through periodic sampling. Interestingly, rapid pressure cooking at 120°C (248°F) can achieve similar gelatin yields in one-third the time, though some argue this compromises flavor development from Maillard reactions.

Nutritionally, gelatin derived from beef tendons provides bioactive peptides that may support joint health and gut integrity. The slow-cooking process liberates amino acids like glycine and proline that are scarce in muscle meats. These compounds form the basis of traditional remedies for arthritis and inflammation in both Eastern medicine and Western "bone broth" trends. However, the actual bioavailability of these nutrients depends on individual digestive capacity and the presence of co-consumed vitamin C for collagen synthesis.

From a sustainability perspective, transforming tough tendons into palatable gelatin represents nose-to-tail utilization at its finest. What was once considered scrap material now commands premium prices in global markets, particularly for pho and ramen establishments seeking authentic mouthfeel. This economic shift mirrors the scientific appreciation for collagen's culinary alchemy—where precise temperature control converts biological scaffolding into gastronomic gold.

Future research may explore enzymatic pretreatment to reduce cooking times or quantify gelatin's role in flavor perception. Already, molecular gastronomy techniques employ extracted beef gelatin for modernist textures while maintaining thermal authenticity. As consumers increasingly value both tradition and science-backed cooking, the humble beef tendon's journey from collagen to gelatin stands as a testament to culinary evolution—where patience and precision transform toughness into tenderness.

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025