The relationship between dough extensibility and carbon dioxide production during proofing is a critical yet often overlooked aspect of artisanal and industrial baking. While bakers traditionally focus on ingredients and mixing techniques, the silent alchemy of fermentation—where yeast metabolizes sugars into CO2—plays an equally decisive role in determining final product quality. This dynamic interplay between gas retention and gluten development reveals why some loaves achieve voluminous openness while others collapse into dense disappointment.

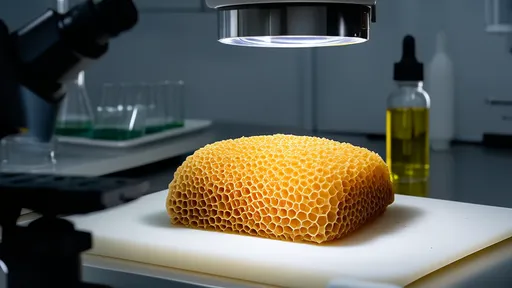

Dough extensibility—the ability to stretch without tearing—isn’t merely a textural trait; it’s the architectural framework that traps carbon dioxide. When flour hydrates, gluten proteins form a viscoelastic matrix whose strength dictates how much gas the dough can retain. Weak gluten (common in low-protein flours or underdeveloped dough) tears easily, releasing CO2 prematurely. Conversely, overdeveloped gluten resists expansion, forcing bubbles to merge into uneven pockets. The sweet spot lies in balanced extensibility, where the dough stretches like a balloon membrane—thin enough to expand but strong enough not to burst.

Proofing time directly influences this equilibrium. As yeast consumes fermentable sugars, CO2 accumulation increases internal pressure. Early-stage proofing sees gradual gas production, allowing gluten strands to reorganize and strengthen. However, extended proofing risks overinflating the dough. The gluten network overstretches, becoming fragile. This explains why overproofed dough often deflates when scored—the structural integrity collapses under accumulated gas pressure. Temperature further complicates matters: warmer environments accelerate yeast activity, shortening the window before overproofing occurs.

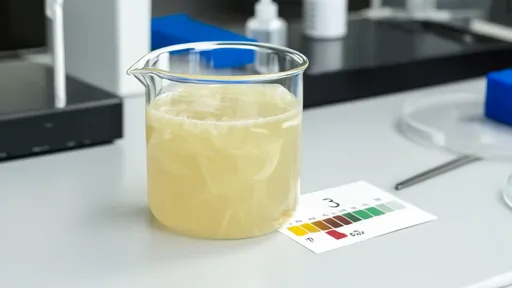

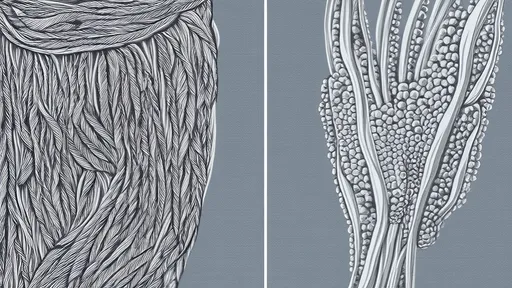

Industrial bakers leverage rheology instruments to quantify extensibility, but small-scale bakers rely on tactile cues. The "windowpane test"—stretching dough until translucent—remains a gold standard. When performed at 30-minute intervals during proofing, it reveals gluten’s evolving resilience. Initially resistant, the dough becomes pliable at peak proof, then turns slack as gluten degrades. Parallel observations of bubble size distribution (via crumb analysis) confirm that optimal extensibility correlates with uniform alveolation—proof that gas retention and gluten development peaked in harmony.

Unexpected variables also intervene. Salt, for instance, tightens gluten but inhibits yeast. Doughs with 2% salt exhibit delayed CO2 production compared to unsalted batches, yet achieve better oven spring due to superior gas retention. Similarly, preferments like poolish or biga precondition gluten for extensibility while jumpstarting fermentation. These techniques demonstrate how bakers manipulate timelines to synchronize gas production with structural readiness—a dance where timing means everything.

The consequences of misalignment manifest vividly in sourdough versus commercial yeast systems. Wild yeast ferments slower, producing CO2 over 12+ hours. This prolonged activity allows gluten to gradually adapt to gas pressure, often yielding superior extensibility. Instant yeast, by contrast, generates explosive CO2 within hours, demanding vigilant monitoring to prevent overproofing. Such differences underscore why sourdough tolerates ambient proofing while commercial yeast doughs thrive under controlled retardation.

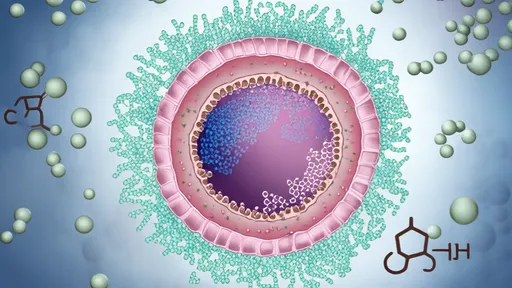

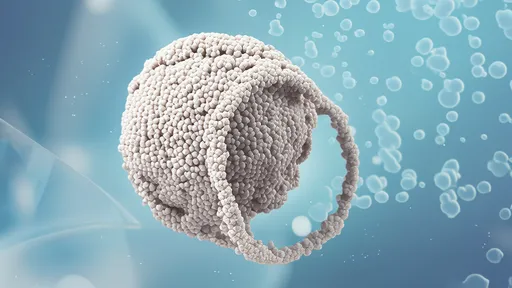

Modern research employs time-lapse microscopy to visualize bubble dynamics during proofing. Footage reveals how CO2 initially dissolves into the aqueous phase before nucleating into micro-bubbles. As these bubbles grow, they push against gluten walls, inducing the stretch that defines extensibility. Fascinatingly, bubbles below 50μm often reunite into larger cavities—a phenomenon exacerbated by weak gluten. This microscopic perspective confirms that gas production alone doesn’t dictate crumb structure; the dough’s ability to manage that gas is equally pivotal.

Ultimately, mastering extensibility and proofing isn’t about rigid formulas. It’s understanding how flour type, hydration, fermentation speed, and mechanical development converge to create a gas-holding scaffold. The baker’s intuition—knowing when to pause proofing based on dough’s tactile feedback—often outperforms algorithmic precision. Because in the end, whether crafting baguettes or brioche, success hinges not just on making CO2, but on building a matrix worthy of holding it.

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025